From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 63 – first published in 2016.

Story and photos Jim Scaysbrook

What could have been the saviour of the venerable Indian marque turned out to be quite the opposite.

The first time I saw a photo of an Indian Scout 249 I immediately thought that the photo had been reversed prior to printing. I mean, primary drive case on the right? But no, this was the real deal, even if things were about-face to usual (that is, British) practice.

The short and anything but sweet saga of the new generation of Indian lightweights – the Model 149 220cc Arrow single and the Model 249 440cc Scout twin – began in 1945 with the takeover of the Indian company by industrialist Ralph B. Rogers. The President of Indian faced an unenviable task, not just in penetrating the market with these most un-traditional offerings from America’s most venerable motorcycle company, but in convincing the ultra-conservative dealers – many of whom had been selling the brand for half a century – that this was a move the company simply had to make. By this time, immediately post-WW2, the old V-twins were well and truly over the hill, but the dealers refused to let go, much less embrace the concept of the new models. The 149 and 249 had been designed in 1944 by G. Briggs Weaver, who had been engaged by the Connecticut-based Torque Manufacturing Company to come up with what was termed a modular engine design that could be produced as a 220cc single, 440cc twin, or an 880cc in-line four. The four never went ahead, but the smaller two did. When Rogers bought out Torque, he inherited the new twins, which were put into production, badged as Indians. Actually, discussion rages as to the actual capacity of these engines, stated various as 23cc, 217cc, 218cc or 220cc; the twin (and the four) being multiples of the same cylinder. Officially, the bore and stroke dimensions were listed at 2 2/3” x 3”, or 67.7mm x 76.2mm.

It was no overnight happening, mind you. Four years of development and testing took place before the new models were finally released in 1949 – a program that chewed through half a million dollars. In a statement to Indian dealers, Rogers said, “In tooling the machines for production, we have made a tremendous bet that we would be successful in selling hundreds of thousands of these machines… The jigs, dies, fixtures and gauges alone have cost $750,000, and we are not through yet. The same exists on plant and machinery. These machines are to be produced in a new plant, engineered solely and wholly for their production. Automatic conveyor lines, rust-proofing installations, the finest painting, baking, and finishing equipment, all brand new, have been purchased and installed specially for these machines. Actually, the total investment involved in the creation of this new Indian Motocycle Company with its new designs today approximates $6,600,000.”

In an advertising bombardment, where the company outspent any other motorcycle manufacturer, Indian signed up Hollywood stars like Jane Russell and Allan Ladd, football and baseball heroes, musicians and other celebrities. You meet the nicest people on an Indian?

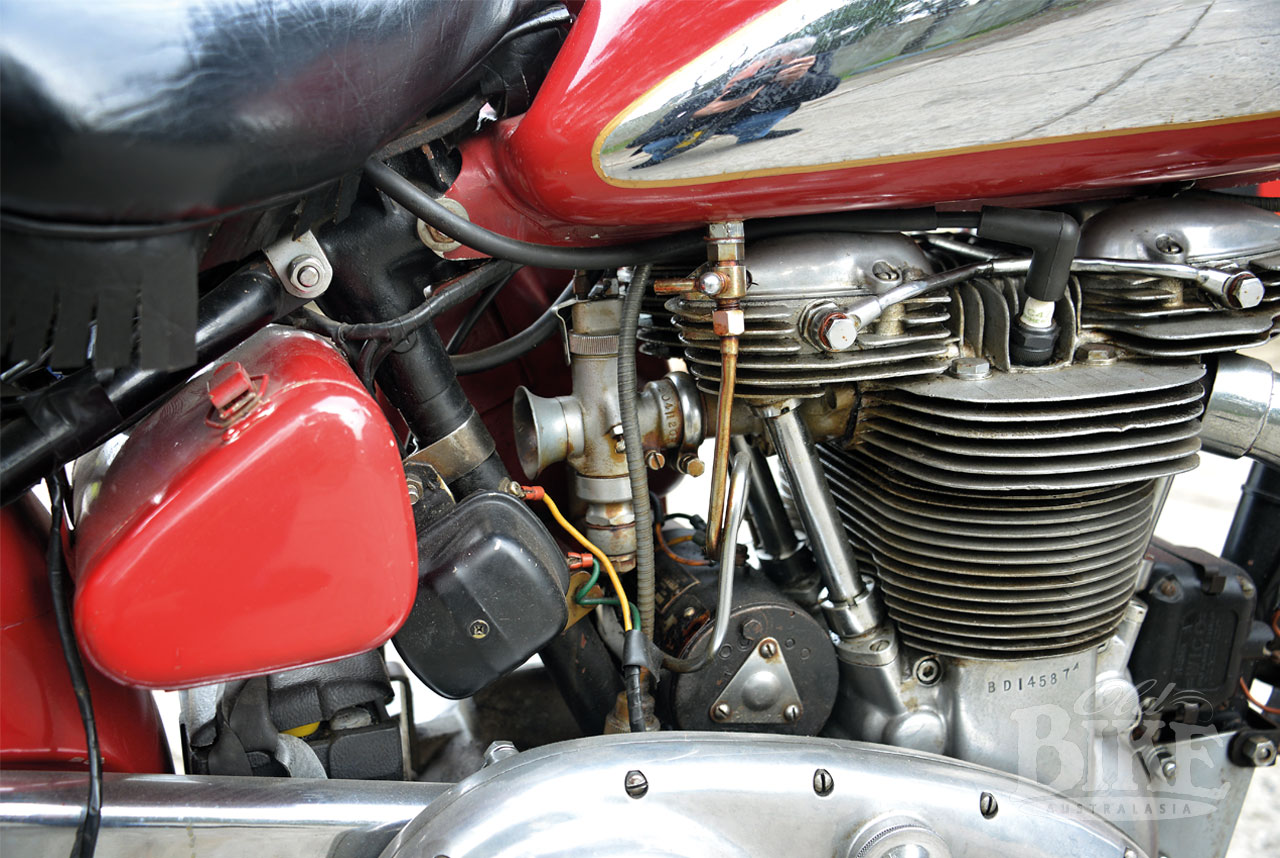

However from the very start, the new models were beset with troubles, not all of them quality related. Component suppliers failed to meet delivery schedules (not just for the new models but for the existing v-twins), causing Indian to lay off nearly one third of their 1650 employees. But there were also reliability issues, encountered as soon as the first of the new models trickled out of the new East Springfield factory. Starting the twin was a particularly onerous chore – a fault traced to the fact that the magneto, which worked OK on the single, was not up to the job when hitched to a distributor. It transpired that for cost reasons alone, the originally specified, high quality magneto had been replaced by a cheaper option. When left standing for even a short period of time, the primary chain case filled with oil, which escaped from the tank via a non-effective ball-valve. After very little running time, the primary chain became slack and noisy, and there was no provision for adjustment!

These were design faults, but there were also numerous quality control problems. Nearly 2,000 bikes left the factory without having the wheel bearings packed with grease, and others had welding flux remaining in the oil tank. Front fork seals leaked profusely. Valve train problems emerged because early and late model gears, which had different pitch angles on the teeth, became mixed up. All these problems came back to haunt the dealers, who became increasingly fed up with the pitiful standards at the factory.

As Indian struggled to sort out these issues, which it gradually achieved, a body blow – completely out of their control – was delivered by the British government, which devalued the pound against the dollar by almost 30%. Overnight, import prices for British bikes dropped by one third, and what little home market share Indian had, collapsed. A further 250 employees received their marching orders, meaning the Indian workforce was now 50% of what it was twelve months previously, with the same sales targets still in place.

Things were getting desperate. Dealers were panicking and customers, even those loyal to the Indian brand, were getting itchy feet. Cash was needed, and fast, so Rogers flew to England in April 1949 for a crisis meeting with J. Brockhouse & Company. Brockhouse was a long established manufacturing organisation which originally made axles and springs. It appears that the company did rather well from the two world wars, snaring lucrative contracts and expanding rapidly into machine tools and castings. It also manufactured the Corgi fold-up scooter which was used extensively by the British military.

Rogers managed to secure a $1.5 million loan, which came with strict conditions. John Brockhouse (son of the founder) received a seat on the Indian board, and the Brockhouse company was permitted to set up a new and independent distribution company called Indian Sales Corporation. ISC would purchase the entire production of the Indian factories and become exclusive distributors for the brand, as well as distributing the British AJS, Douglas, Excelsior, Norton, Royal Enfield, Vincent and Matchless in USA. John Brockhouse wasted no time in asserting his authority, and one of his first moves was to fire Rogers, which occurred in January 1950.

Although the new Arrow and Scout models were significantly improved for 1950, Indian dealers around the country were stocked up with the slow-selling earlier models. Still, the factory was churning out the singles and twins at the rate of 250 a month, the line now including the Warrior and Warrior TT – an up-spec Scout punched out to 500cc with a larger Amal carburettor fitted. Retail prices for the existing stock were slashed by 25%, but this had little effect. The Warrior TT was a higher performance version designed for enduros and Flat Track (TT) racing, and the model received a shot in the arm when Joe Gee won the 1951 Jack Pine Enduro on one, ending a string of 25 consecutive victories by Harley-Davidson.

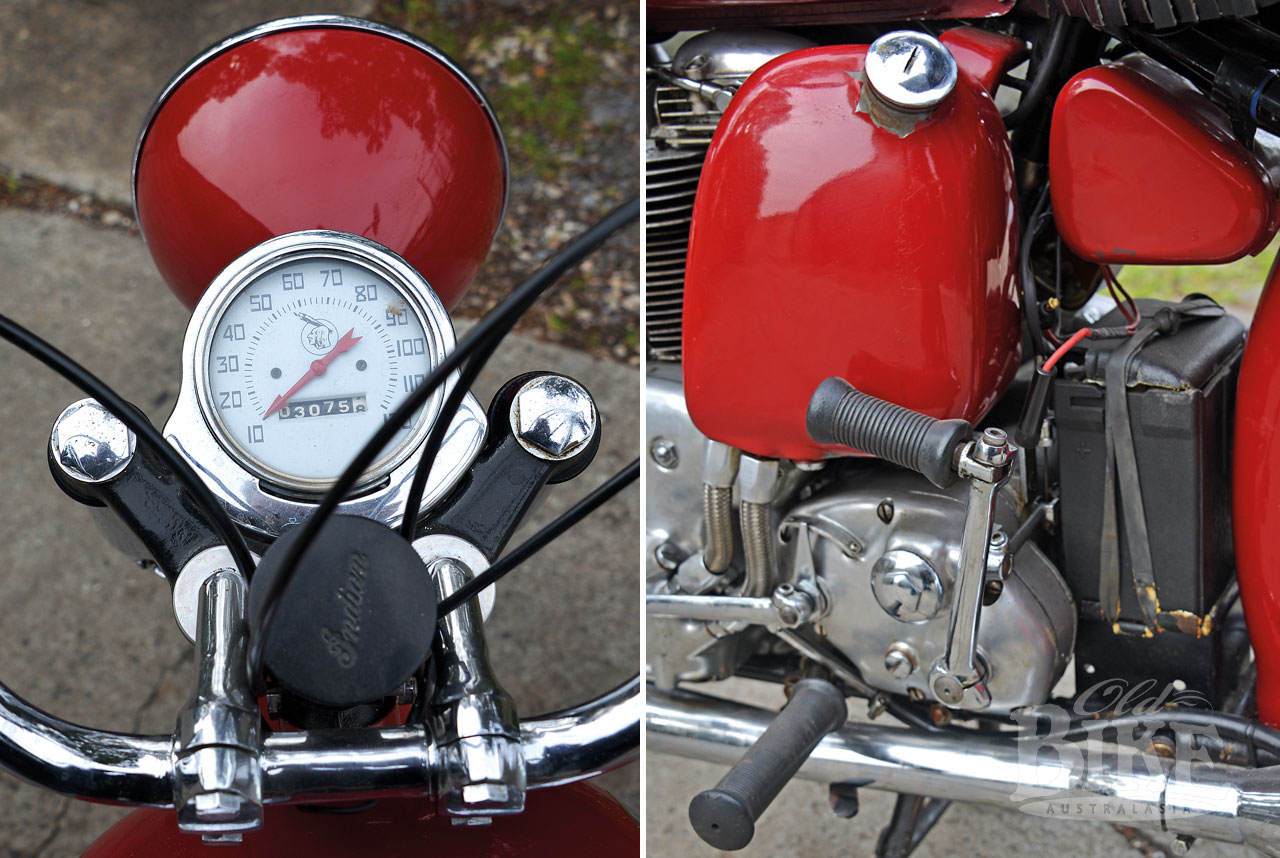

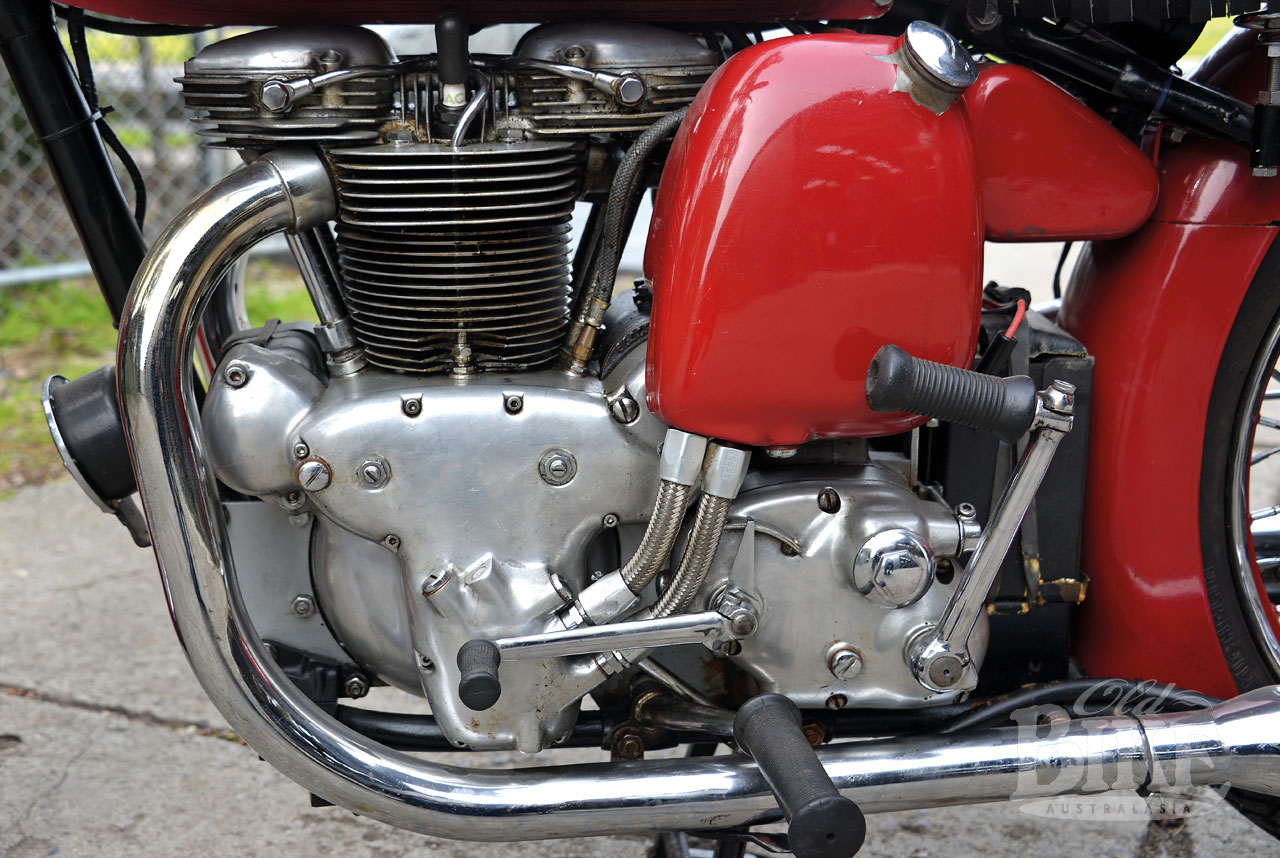

The 249 up close

As delivered in 1949, the Model 249 Scout was, on paper at least, an interesting and relatively up to date design. Unlike its British rivals (*except for the Triumph T100) the engine was all-alloy, and the quality of the castings was first class. These were the first US-made motorcycles to be fitted with a left-side, down for down gear change, with the rear brake on the right hand side. The kickstarter was also on the left. Reputedly, the 440cc twin put out 20 horsepower and weighed 127 kg, which put it well behind the British 500 twins in performance. A single carburettor was fitted and it was virtually impossible to fit twin carbs, as the pushrods were splayed from the crankcase to the ends of the rockers, and on the inlet side this severely restricted the amount of metal around the inlet port. Each pushrod operated on its own camshaft. Bolted to the rear of the engine was a four-speed gearbox.

The Scout was sold in three models, the basic Scout, the Super Scout, and the Sport Scout, each differing slightly in the level of standard equipment. The chassis was, at least by Indian standards, fairly modern in concept, with oil-damped telescopic front forks and a plunger rear end. A sprung saddle was standard fitment, with a tubular steel luggage rack attached to the rear mudguard. Frames were painted in the same colour as the tank and mudguards, with a black headlight shell. Top speed was said to be 85 mph.

The later Warrior, with its full 500cc capacity and most of the earlier faults addressed, was a far better motorcycle, and with a black-painted frame, actually looked more conventional. But the damage done by the earlier unreliability was fully entrenched by the time the Warrior appeared in 1951, and only about 450 were built before Indian ceased production at its Springfield, Massachusetts factory. As well as increasing performance, increasing the capacity of the Scout/Warrior from 26.6 cubic inches meant the model was eligible for AMA racing, as rules stated that the minimum capacity was 30,5 cubic inches (500cc).

For 1951, a Police model Warrior was produced, with a raised sprung saddle and footboards instead of footrests, and with larger, heavily valanced front and rear mudguards. Although several prototype versions of the roadster warrior were built for the 1952 year, production of this model was cancelled and the Warrior produced in only the TT version, and only a handful of these made it into metal before Indian collapsed in 1953.

The featured motorcycle here is a 1949 440cc Model 249 owned by Zorros in Melbourne. In completely original specification, it is a very rare machine Down Under and owner Mark Barthalmie believes it may well be the sole example in this country.

Please note that this article is from our Old Bike Archives – Issue 63 – first published in 2016.