From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 64 – first published in 2017.

Story: Peter Laverty Photos: Independent Observations.

There is probably no better example of how competition improves the breed than the Yamaha RD400. And while it can be said that the 400 owes much to the RD350 it replaced (which in turn owed quite a bit to the preceding R1 through to the R5), it really seemed a quantum leap at the time.

The RD350 did immeasurable good to make road racing affordable for the average Joe; it was fast, reliable and handled adequately – just the kit to get your rocks off on weekends. More than a few play racers on RD350s graduated to bigger and better stuff; it was the perfect machine to show up natural ability, or lack of it. The RD350 sold phenomenally well around the world, even in USA where the Honda CB350 had been the chart topper for several years.

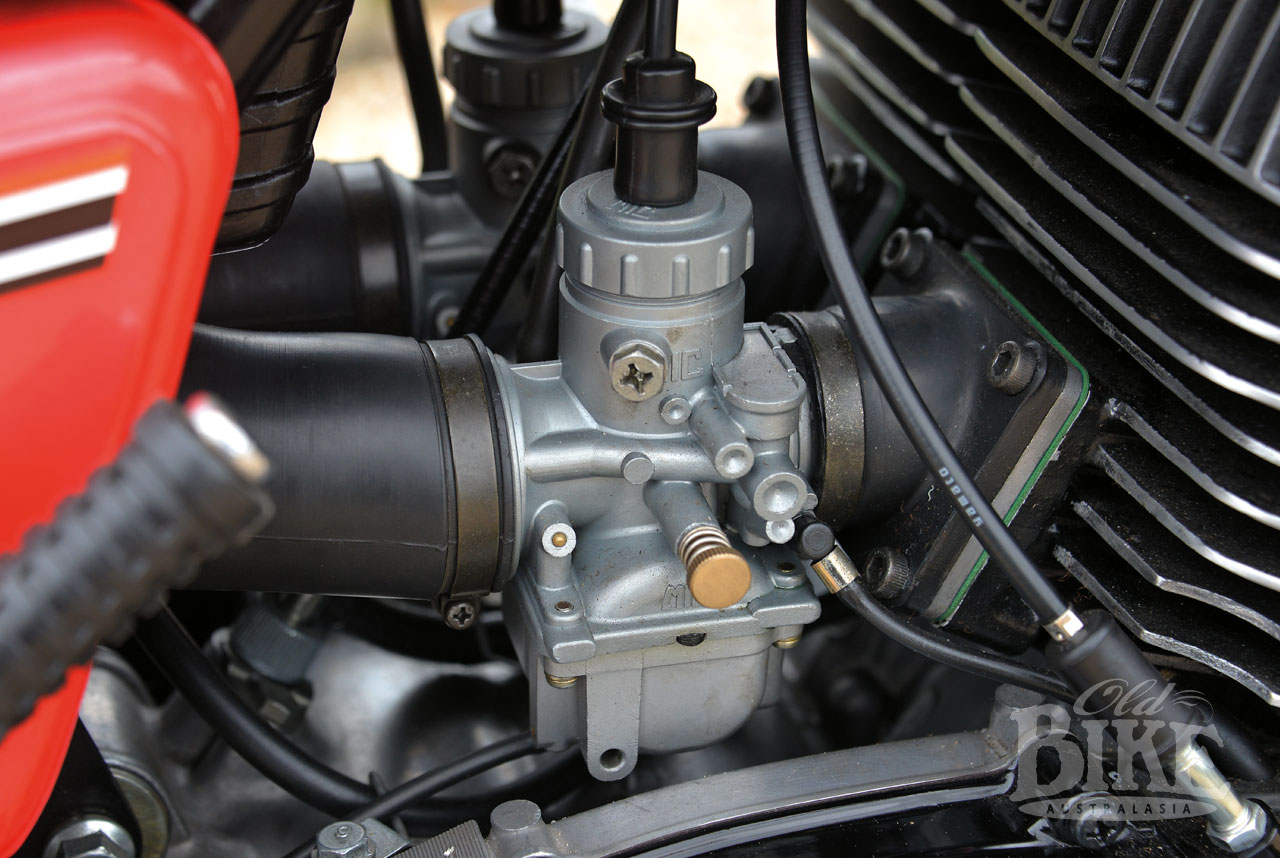

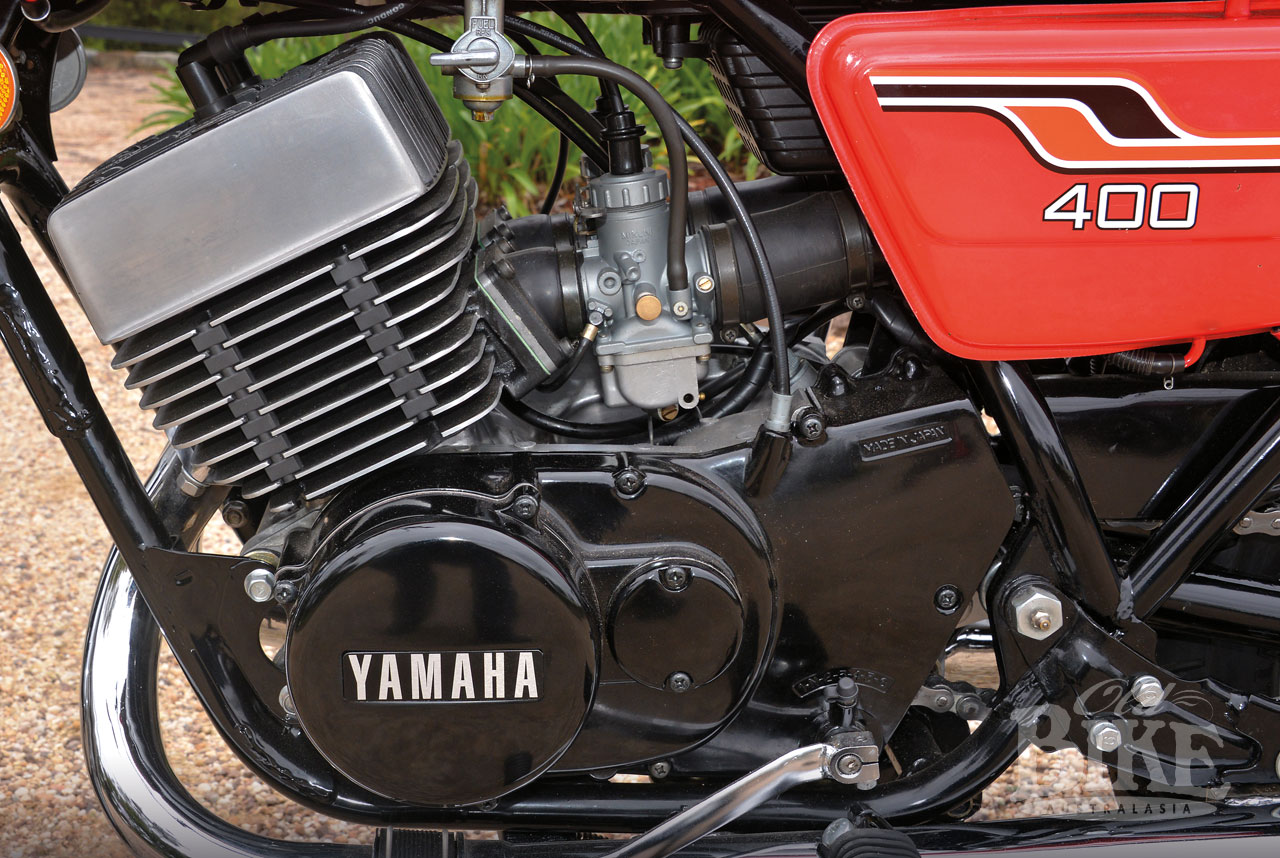

But in reality, and in detail, the RD400C was virtually an all-new motorcycle, beginning with the engine. Instead of taking the easy route with the boring bar, Yamaha left the cylinders with the same 64mm bore as on the 350, but produced a new crankshaft with 8mm longer stroke. This took the capacity from 347cc to 398cc, and amped up the associated power and torque figures along the way. To accommodate the new longer stroke crank were new crankcases, still containing four main bearings, one at each end and two in the centre. A novel (for Yamaha) feature was a small hole in each cylinder, just above the exhaust port, running at 45 degrees back into the exhaust port itself. The theory behind this was to smooth out low speed running and to make starting easier. A further innovation to help reduce surging at low revs was a modification to the leading edge of each piston skirt, raising it just enough to permit a very brief period (immediately before and after top dead centre) when the crankcase transfer and exhaust port were directly connected. From all accounts, this thinking worked, the 400 being a much more tractable proposition in the lower rev range than the 350. The new Mikuni carbs probably helped in this respect as well, being easier to tune. Cylinder heads were new, made of thicker section which allowed 17mm reach spark plugs.

The gearbox, while still a six-speeder, has higher ratios for the lower three gears and closer spacing for the top three. Primary drive gear ratios were identical to the 350, with a slightly strengthened clutch to cope with the extra power. Behind the clutch was a larger shock absorber.

The 400 used basically the same frame as the 350 in terms of overall dimensions and steering head angle, but with the engine set 20mm further forward, putting more weight on the front suspension, which coped only marginally well. To compensate for the front weight bias, the swinging arm was lengthened slightly. One change was to the middle section, which needed to cope with the larger air box required by the 400. This new air box also reduced intake roar a little. The engine was also rubber mounted (although not on the almost identical RD250), using radially-vaned blocks separated by spacers. This required a flexible, rubber sleeved union between the engine’s exhaust pipes and the mufflers, which are mounted directly to the frame with no flexible mounting. Footrest plates were also rubber mounted to minimise any tingles through the footrests themselves, and the handlebars were also rubber mounted.

A universal criticism was the stock Japanese Yokohama tyres and these were usually ditched long before they had worn out, in favour of Metzelers, Avons or Dunlop K100s. Visually, the 400 (and the sister RD250C which shared virtually all components) was distinguished by the cast alloy seven-spoke wheels, which although slightly heavier, needed none of the maintenance of the former steel rim and spoke jobs, although on the original RD400C, spoked wheels were still fitted in some markets and were standard on the near-identical RD250. The alloy wheels, manufactured for Yamaha by Kobe Steel, were the first cast wheels to be fitted to a mass-produced motorcycle.

Of course, minor tuning was needed to get the best out of the new machine. Heavier fork oil was also called for early in the life of a new 400, 20 weight or automatic transmission fluid instead of the supplied 10 weight being the usual recipe. Pretty soon, there were several brands of heavier fork springs on the market as well. Japanese rear shock absorbers of the day (in this case Kayaba) were still lowly regarded, and Koni, Mulholland and Girling did a good business in supplying after market units. Although the front disc and brake caliper are the same as fitted to the earlier 350, the caliper itself was moved to behind the right side fork leg rather than in front, a move the manufacturers claimed to ‘reduce steering inertia’. Both discs were of 220mm diameter.

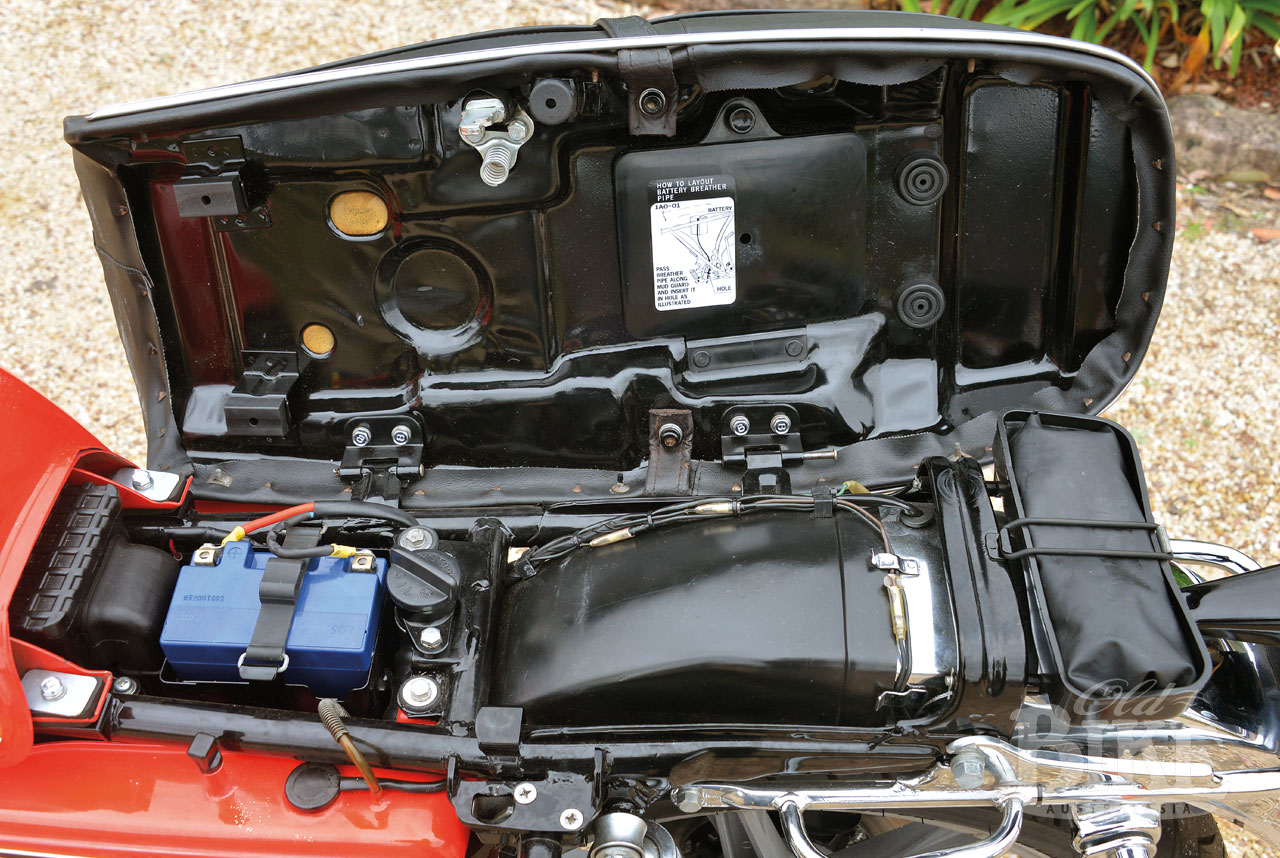

The 400 ushered in a completely new styling package that was to carry over to other models in subsequent years. A much more angular design, the fuel tank had slab sides and a flat top, while the side covers were also squared off. The seat was also more lavishly padded, being about 25mm thicker than the 350’s. Instead of the window in the side cover to check the level for the oil being fed to the injection pump, a warning light came on in the instrument panel. The tank was also equipped with a dip stick to monitor the level. When full, the oil tank would allow nearly 500km before needing to be topped up.

One feature that everyone seemed to like was the new self-cancelling turn indicators. Some previous versions had been timed, but the new system incorporated a 15 second period, and/or a distance of approximately 150 metres. After being activated, the lever automatically returned to the central position and could be manually cancelled by pushing it. What everyone didn’t like was that this feature seemed to go awry fairly quickly, necessitating either a new, genuine switch block, or, more likely, a return to totally manual operation.

While the overall handling was deemed quite acceptable, one feature that limited cornering ability was the fact that the footrests ran around, instead of behind, the mufflers and were easily grounded. At $1195.00 plus registration, the RD400 sold extremely well in Australia, and although the increase in capacity meant it was no longer eligible for the 350 class in club racing, it mattered not as it was more than competitive against the 500s. As a commuter, the RD400 was a much better proposition than the 350, the mods to improve low end power and reduce the tendency to surge producing a much more refined package.

A brighter spark

Within 18 months, Yamaha had a revised RD400 on the market – the RD400E. There had also been a D model following the C, but to all intents and purposes the two were identical in all but graphics and paintwork, and retained the battery and points ignition. But by 1978, ‘electronic’ was the buzz word in the ignition world, especially when applied to two strokes. E was the logical progression in the standard Yamaha model lineage, but it could have also represented E for Electronic, for this model dispensed with points and instead sported CDI ignition. A single coil replaced the twin coils, and Yamaha claimed the new system was truly ‘set and forget’, unlike the C and D models which were prone to plug fouling and fairly short plug life.

There were also important detail improvements, such as bigger 35mm front forks with 140mm travel instead of 120, and – for the scratchers – footrest mounted inside the mufflers rather than outside. Hanging off the front forks was a bigger 265mm front disc, clamped by a single-piston floating calliper. The wheels were also slightly changed with thinner spokes, and hence were lighter. Inside the engine, substantially revised porting gave a ten per cent increase in power output to 44bhp at 7,000 rpm. The engine mods consisted of altering the shape of the ports, extending the inlet and improving scavenger via new pistons. Greater volume silencers also contributed to the power increase. Carbs remained at 28mm but were now joined by a balance pipe and main jets were up from 120 to 145.

Colour schemes varied from market to market, but a popular décor was the white and red which mirrored the factory racers and the production TZs. The 1979 RD400F was the last of the line, and essentially the same as its predecessor. The seat and rear end styling also came up for revision, with a ‘duck tail’ lip on the rear of the seat.

Today the RD400 – from the first C to the final F – is a highly sought-after motorcycle, provided you can find an unmolested one. This is trickier than it may seem, because the 400 was often pressed into service on the track, and modified both internally and externally to suit. Reverse engineering this process needs patience as some major components, such as cylinder blocks, are hard to come by. But properly set up, any of these models makes an excellent rally bike – fast, reliable and light – with good manners and minimal maintenance required, at least on the CDI models. The general consensus is that it is a better all round proposition than its two main rivals – the Suzuki GT380 and Kawasaki KH400 triples with conventional piston port induction as opposed to the Yamaha’s reed valves. The Yamaha system has a big advantage in that it prevents the old two stroke bugbear of blow-back through the carburettors and inlet tract, which is both wasteful of fuel and annoying.

We are indebted to David Aquilina for the opportunity to photograph the RD400C that he has recently restored. David has fastidiously rebuilt the bike using genuine NOS Yamaha parts, including rubbers and switch gear and original mirrors, many of which came from Steve Inskip Motorcycles in Toronto, NSW and Greg Penna in South Australia. The paintwork and graphics on the petrol tank are actually original, but the top section of the tank had faded so David had it resprayed – an excellent job that is indistinguishable from the original. Mufflers were rechromed and the seat recovered over the original base which was in good condition. The frame was repainted in 2-pack, rather than being powder coated. The complete engine rebuild, including big and little ends, pistons and rods was undertaken by Dudley Lister at Wyong, NSW, and David says he couldn’t be happier with the result.

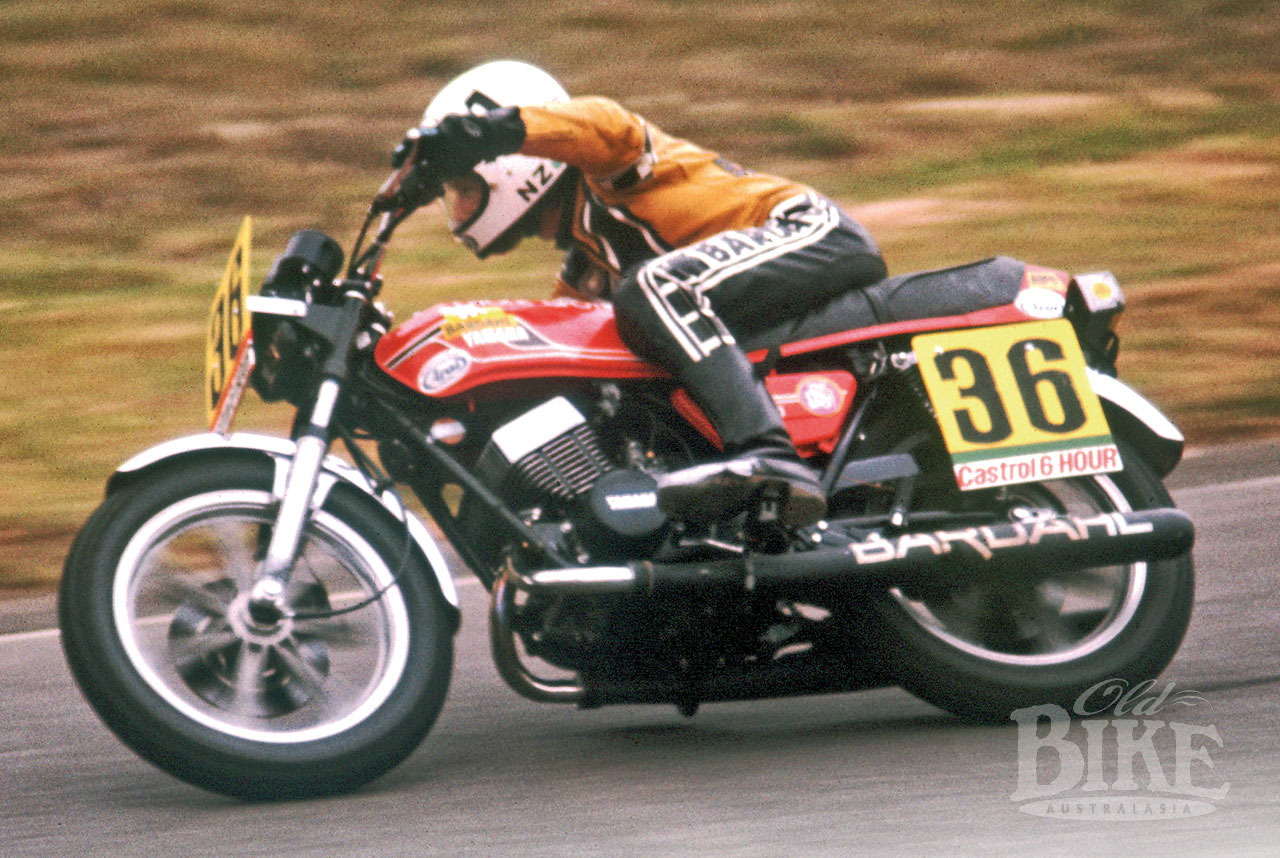

Not bad on the track, either.

The 1976 running of the Castrol Six Hour Race saw five RD400Cs entered. The individual capacity classes for 250cc, 500cc and Unlimited had been dropped the previous year in favour of an all-in Unlimited class, but there were many who figured that a well ridden RD400 could be quite competitive over the race distance due to the ability to conserve tyres and brakes. One factor that was clearly against them however was ground clearance, the right hand footrest bracket dragging on the ground for much of the lap. Nevertheless, Murray Hill and Shayne Laurent brought their RD400 home in 14th place outright on 336 laps, easily accounting for the rival Honda CB400F entries. Two other RD400s finished, Michael Kane/Gary Middleton in 24th on 321 laps, and Glenn Rohwer/Michael O’Meara/Peter Walker in 27th on 299 laps. The following year Hill teamed with Martyn Aiken and was again the top placed 400, in 15th place on 337 laps.

The beginning

The RD400’s lineage goes all the way back to the mid ‘sixties. With the success of the 250 cc twins, it was logical that Yamaha would eventually up the ante and produce a machine for the 350 cc category. That machine first appeared in limited quantities in 1965 as the R1, sporting the company’s new Autolube system that did away with petrol oil mixing. Aimed directly at the US market, the R1, and the virtually identical R2 actually had a capacity of 305 cc, producing 36 hp which would propel it through a standing quarter mile in a very respectable 14.8 seconds. Within two years a full 350 – the R3, appeared. The original R1 had a factory-claimed top speed of 105 mph and a cross-over gear shaft to allow either a left or right foot gear change. The R1 was good, but the subsequent R3 was much better; the five-port barrel, utilising two extra transfer passages, considerably enhanced performance, and crucially for the US market, produced a cleaner exhaust with less unburnt fuel and lower emissions. The R3 itself gave way to the R5 in 1970.

Specifications: 1976 Yamaha RD400C.

Engine: Air cooled two stroke twin cylinder with reed valve induction. Alloy head and barrel.

Bore x stroke: 64mm x 62mm. 398cc

Compression ratio: 6.2:1

Power: 40bhp at 7500 rpm.

Torque: 38.2 Nm at 7000 rpm.

Carbs: 2 x VM 28C Mikuni

Transmission: 6 speed gearbox, wet clutch. Chain final drive.

Suspension: Yamaha telescopic forks and Kayaba rear units.

Wheelbase: 1315mm.

Ground clearance: 155mm

Brakes: Single disc front and rear

Wheels: Cast alloy wheels with 3.25 x 18 front and 3.50 x 18 rear tyres.

Weight: 156.5kg.

Fuel capacity: 16.5 litres

Oil capacity: 1.8 litres

Top speed: 166 km/h.