The rain eases a few minutes short of midnight but has already saturated the small knot of officials – their timesheets a sodden mess. A puff of wind does little to disperse the fog as the temperature drops to single digits. Hell hasn’t frozen over but there’s still time. “Thirty seconds” says the starter as Charlie Moyle and Dick Brown prime themselves to heave the A.J.S. outfit down the slippery tarmac to bumpstart the 500cc single. Fortunately it cooperates and they scramble aboard to be swallowed by the fog. A squall of rain follows. Twenty four hours later they’re back, having ridden and otherwise manhandled the A.J.S. over 400 miles along the primitive byways surrounding the city to win the inaugural ‘Adelaide Register 24 Hour Reliability Trial’.

Story: Peter Whitaker (from OBA Issue 35 – November 2012)

Residents on the windward fringe of the Great Southern Ocean realise the June long weekend isn’t conducive to motorcycling and, as the coldest hours are just before dawn, dropping the green flag at the bewitching hour bordered on sadism. But in the City of Churches, young bloods on motorcycles were barely tolerated at all so a competition on Sunday, to be held on public roads no less, would be sacrilege. However, Adelaide’s leading newspaper ‘The Register’ supported Wal Murphy, President of the Motor Cycle Club of South Australia, and despite the naysayers and knockers the inaugural 24 Hour Reliability Trial took place on the Holiday Monday June 1924. For the stragglers facing the bundy on Tuesday would be a tough ask.

Though fewer than fifty competitors took on the challenge with only ten finishing, there were thousands of spectators surrounding the most formidable obstacles along the course and, with over thirty controls organised by the district motorcycle clubs, officials outnumbered participants four to one. Nonetheless the event was considered a resounding success by ‘The Register’ providing excellent fodder for the entire month as the results were discussed and dissected in various watering holes around town.

In an era when motorcycles vastly outnumbered automobiles and ‘outfits’ were as common as model ‘T’ Fords, few enthusiasts could afford to risk their daily transport in an event where the five guinea prize would barely pay for fuel and tyres. Thus ‘24 Hour’ competitors were usually spoken of with the same reverence as test cricketers and VFL stars, though there were some citizens, such as those that threw upturned horseshoes across the route, vehemently opposed to the speed demons.

In fact, with a moving average of less than 20 miles per hour, and top speeds barely approaching twice that, the actual event was extremely well modulated. However with the course details published weeks prior to the event it’s possible that reconnaissance caused some angst among the populace in the small hamlets along the route. Pre-riding the course was encouraged as during the actual trial there would often be zero visibility in the fog. At night competitors approached such notorious sections as Carey’s Gully with great trepidation, if not abject terror.

For four years the ’24 Hour’ became Adelaide’s winter sporting highlight with many of the same stalwarts battling the elements along the rudimentary tracks, coping with swollen creeks, fallen trees, and rutted stock routes cut up by the winter rains. Eventually the Church Elders realised that such a small group of reprobates – however popular with the hoi-polloi – were not about to entice their flocks down the road to perdition and allowed the 1929 ‘24 Hour’ to be held on the Sunday. Eight solos and a dozen outfits faced the starter which was renamed ‘The Advertiser 24-Hour Motor Cycle Endurance Contest’ as the organisers struggled to strike the right balance between plotting a course that could be achievable and one that would become an absurd nightmare with the lightest shower of rain.

Despite coating the rudimentary electrics in beeswax and plasticine, sealing the oil tanks, encasing cables with inner tubes, and fabricating makeshift ‘snorkels’ from the carburettor to the handlebars, the machines became so waterlogged that trackside repairs were unthinkable. With ‘outside assistance’ forbidden, the rider was forced to divest himself of oilskin laprug, sodden leathers, greatcoat, welder’s gloves and fishing waders simply to have the mobility to shift his stricken mount. To avoid hypothermia, oilskin handle bar muffs connected to the exhaust proved popular and one competitor experimented with a prototype ‘Driz-a-Bone’ lined with plastic tubing to funnel exhaust gases who knows where. Rain free events were less devastating, the most common problems being dusted engines; the primitive air cleaners fashioned from womens undergarments rarely proving effective.

With a mechanical failure rate over 70% invariably it would be the Harley or the Henderson, the Douglas or the New Imperial that would break, shatter, bend or blow up long before the iron men that rode them surrendered to the elements. However dusted engines, blocked nasal passages and parched throats aside, a dry trial would see as many as eleven competitors finish without loss of points, sharing the meagre prizemoney and engraving space on the Perpetual Shield. But rain would turn the best laid plans into chaos as described in the contemporary press. “The worst of the course was the 14 miles of foot deep slush at the dreaded Salters Creek but beyond Dingabledinga the vilest forms of surface gradients and twists conspired to overwhelm competitors leaving only three survivors.” But way beyond Dingabledinga even worse events were unfolding as the Germans overwhelmed Poland.

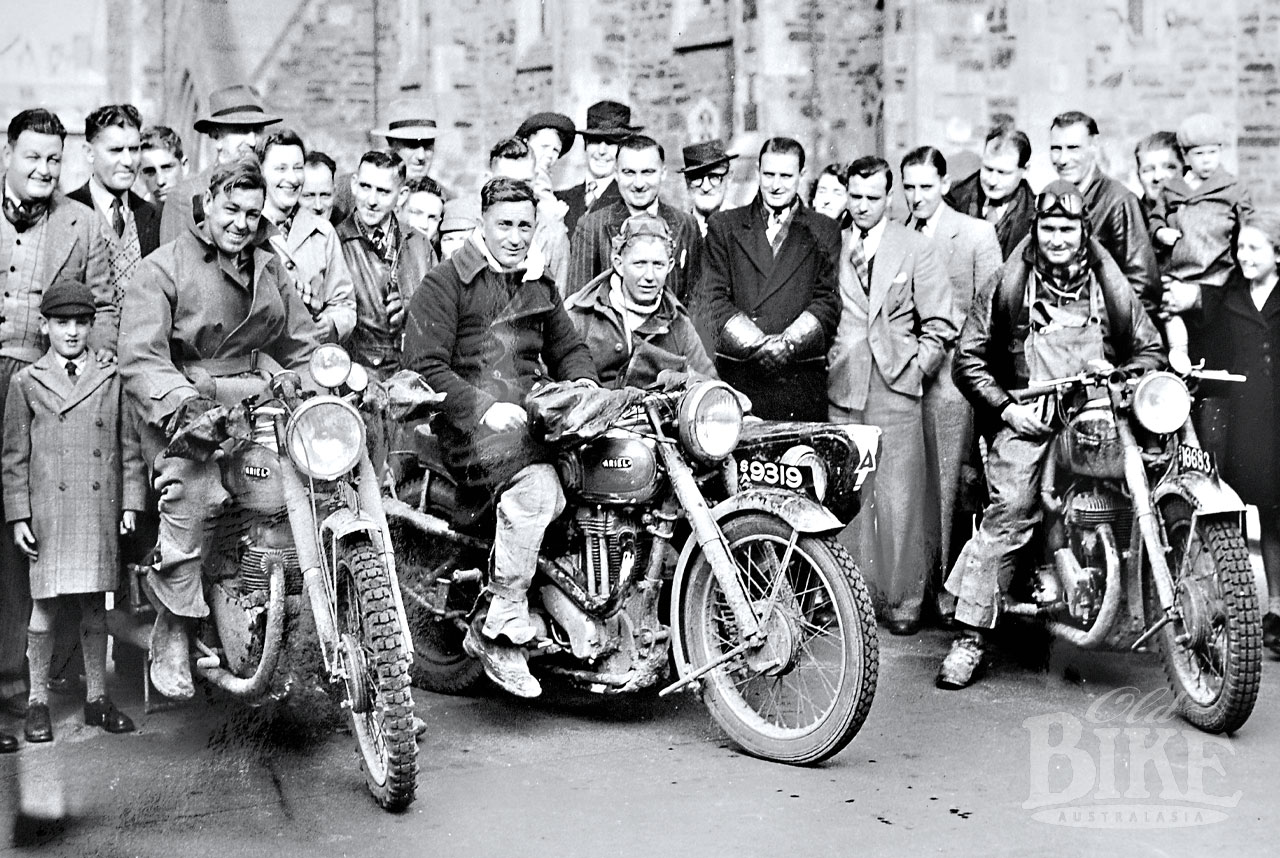

Seven years later the Nasties had been defeated and the Japanese had been incinerated with astonishing new technology; but the lower end of the Murray River was in a time warp as the same familiar characters remounted their same well fettled mounts. With little more than a tank full of black market petrol, fresh Castrol and the last of the pre-war Dunlops, Les Frederick’s Triumph, Ern Holyoak’s Norton and Ron Badger’s Ariel outfit dominated proceedings when Wal Murphy and his supporters revived the ’24 Hour’ in 1947. Post war motorcycle sales skyrocketed with the import of big twins from Ariel, BSA, Matchless, Norton and Royal Enfield. Now with telescopic front forks and plunger rear suspension these state-of-the-art machines saw sales quadruple between 1946 and 1950 – however few owners wished to trash their pride and joy in an event such as the ’24 Hour’.

In 1951, when regular competitor Ron Ophel surveyed an 825 mile course that looped to the far extremes of Orroroo, Renmark and Victor Harbour he predicted that, should it rain, few competitors would reach the half way mark. Not surprising then that only 25 riders signed up for the challenge – a ‘special’ 36 Hour Trial to commemorate Federation. Nor was it surprising that Ron Ophel and ‘Milky’ Reed finished ahead of the only other outfit to survive the ‘36 Hour’ – with perennial champion Les Fredericks winning the solos. Even with some leapfrogging the organisation required to establish almost 50 time-controls using only public pay phones for communication was a logistical nightmare but the event had evolved into a great excuse for sundry groups of mates to light a fire on the outskirts of town, get on the turps and participate in some bench racing.

It would be drawing a long bow to suggest the Holden killed the ‘24 Hour’ but by the time ‘Australia’s Own’ was introduced the number of cars in South Australia had already surpassed motorcycles. Two years later annual car sales had jumped to 20,000 – greater than motorcycle sales for the entire decade – and the public became enraptured by the notorious Redex trials which became front page news across the nation. The ‘24 Hour’ organisers persevered but were finally forced to admit defeat in 1957 when only 17 entries were received and a splendid chapter in Australia’s motorcycling heritage appeared to come to a premature finale.

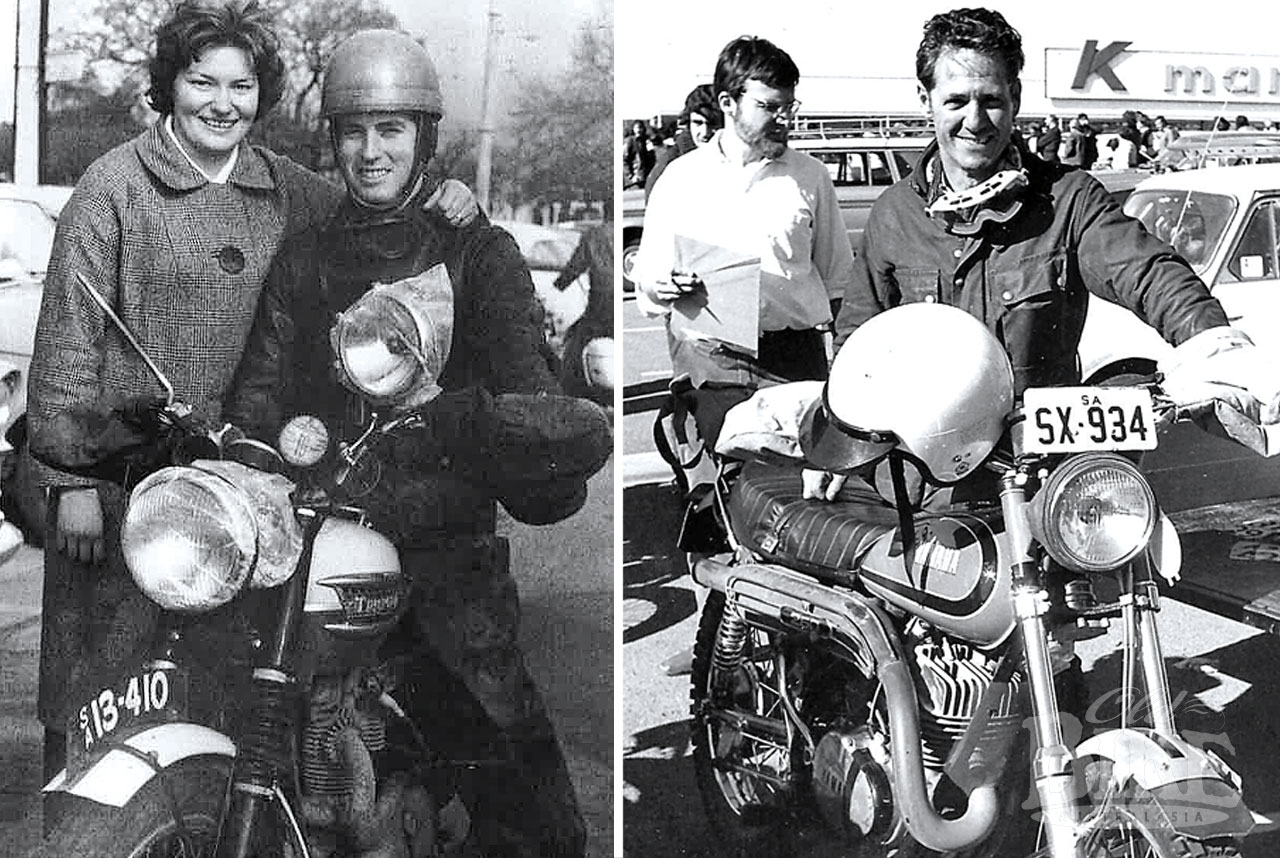

Though the motorcycle industry remained in the doldrums and the public remained focussed on the Redex Trials, the Ariel Motorcycle Club, backed by ‘The Advertiser’ resurrected a more competitor friendly event by surveying a 12 hour route offering riders a choice of one or two laps. Thirty riders – including the first ever female competitor – entered. The 1959 route still utilised unsealed public roads but the time allowances were somewhat more generous and the trial was held in spring, making life a little easier on the rum for the club officials. The revamped ‘24 Hour’ proved a great success, not least because mechanical reliability had vastly improved; among the finishers was Terry Holding, whose Honda Dream was the first Japanese bike to join the winner’s list.

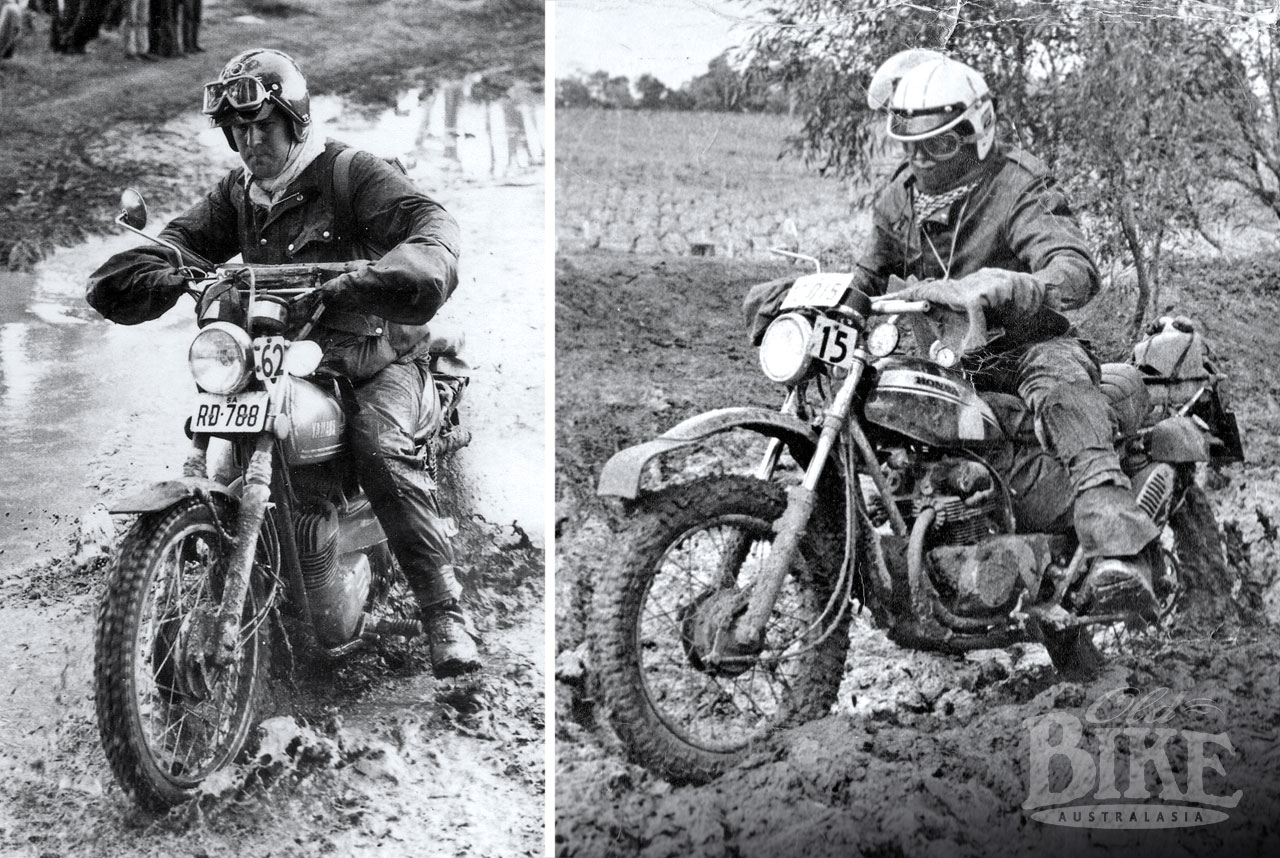

Thanks to the machinations of Hollywood, a few ratbags, and the ready availability of reliable secondhand cars, motorcyclists were now seen as road rebels. Though motorcycle racing in its many forms remained extremely popular it often attracted unruly spectators and unwarranted attention from the wallopers. Not so the ‘24 Hour’ which, under the auspices of the Ariel MCC and ably assisted by a host of Barossa Valley clubs, built a reputation as an extremely family friendly event. Only once, in 1963, did the course become reminiscent of the notorious 1930s as rookie Lew Dowsett recalls “conditions were so bad only 4 riders finished the first lap. Peter Millstead on a Triumph 650, Jim Dowsett on a 500 Triumph, Lloyd Laing on a 500 BSA, and myself on a 350 BSA. Only 3 of us started the second lap, as Lloyd could go no further; the mud had worn all the teeth off his front sprocket.

I pulled up at the Sheoak Log Ford to find it almost breaking the banks! Peter Millstead was on the other side dewatering his bike and I figured if Peter had got through, so could I. how wrong I was! I got half way across and the motor stopped. There I was in the middle of a raging torrent and I went over, ditched the bike and made for the bank. I finally made it however the bike had gone over the slipway and into about 10 feet of water. The second lap was the last of the 24 that year as with only 1 rider still running the organisers declared Peter Millstead the winner.”

Most other years many riders finished without loss of points and, when Ruth Franklin finished the ‘24 Hour’ on a CZ125 and champions such as Millsteed and Weichart ran four events without losing a single point, it was time to ‘toughen up’ the forty year old event. So, with the introduction of the reliable and purpose built ‘trail bikes’, exemplified by the Yamaha DT1, came the introduction of the ‘uncleanable section’ with the intent of eliminating tied-scores. And thus, the reliability trial, with its earlier emphasis on mechanical reliability morphed into a test of rider skills and stamina – literally the forerunner of the enduro – though still utilising the generally accepted trials regulations based on road registered production motos.

The ‘new look’ trial would consist of five laps, still held on unmaintained public thoroughfares, but with the inclusion of three impassable sections – one of black ooze and two of deep choppy sand – all with impossible time allowances; thus ensuring the difficulty of the course reflected the improvements in motorcycle design and rider equipment. Road bikes with modified exhaust systems, re-engineered suspensions and ineffective breathing no longer cut the mustard alongside the Japanese imports. Even the ‘outfits’ with their custom built chassis benefited from reliable 600cc thumpers from Yamaha and Honda. It no longer made sense for enthusiasts to persist in constantly rebuilding doomed marques such as BSA, Matchless, Norton, Velocette et al and given the reliability and low cost of off-the-showroom-floor Japanese (and latterly European) ‘off-road’ models, interest in the ‘24 Hour’ grew exponentially.

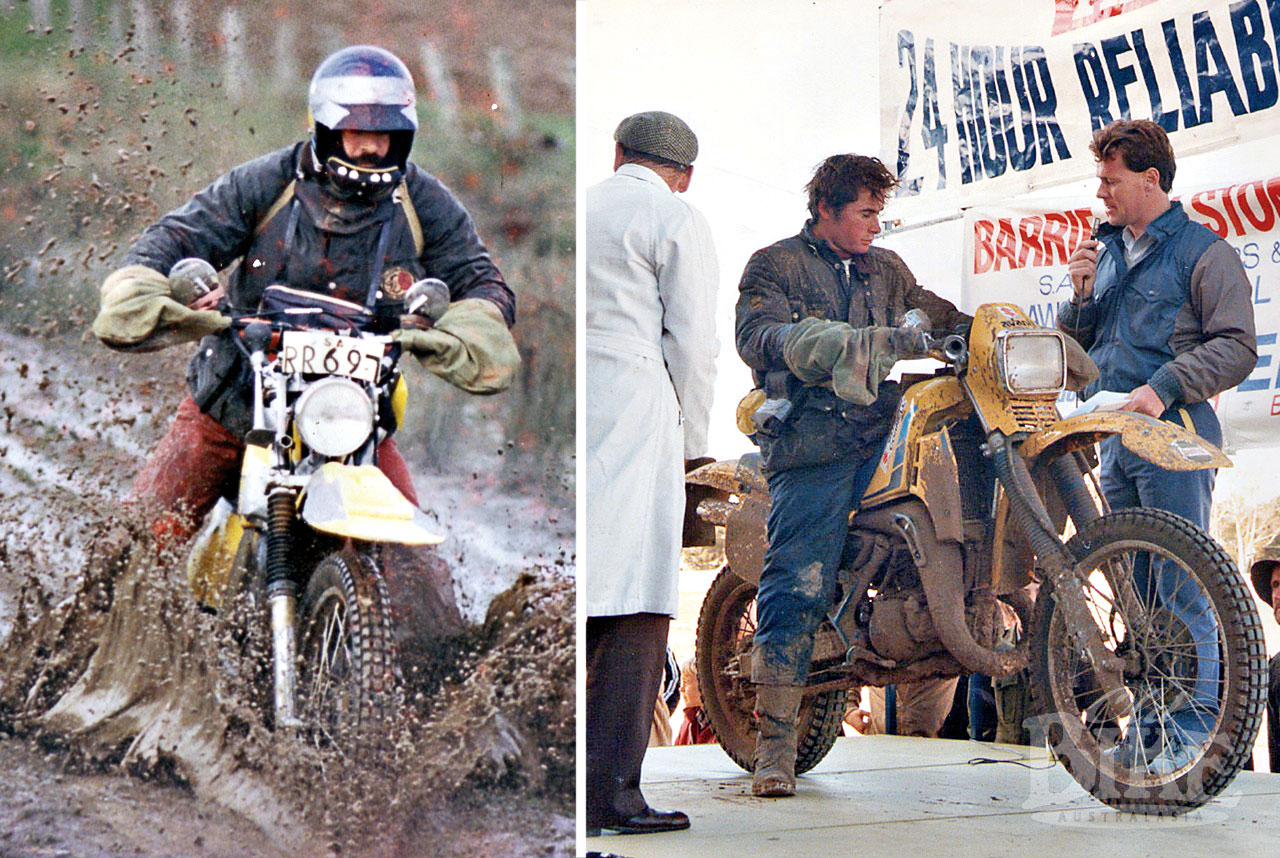

Based in the Barossa with a thriving network of local motorcycle clubs the ‘24 Hour’ re-established itself as a staple on local dirtshifters’ calendars. Inarguably Australia’s oldest and longest running motorcycle race it now attracts discriminating competitors from interstate and overseas. Call it a trial a rally or an enduro it’s now an amalgam of butt puckering thrills and spills interwoven with some tricky navigation to keep the riders alert on liaison sections. The motos, now with stators capable of powering aircraft landing lights, tyres that will claw through the sloppiest cowpats, impenetrable mousse tubes and adjustable suspension systems that remove most of the pain from the rockiest terrain and, mostly piloted by well hydrated quadathletic, riders the Swann 24Hour is a totally different animal than that envisaged by Wal Murphy back in 1924.

It may sound a bit soft when compared to the tough old days until you consider that contemporary competitors hit speeds that can induce frostbite in less than 15 minutes – an affliction that once took all night. Throw in some rain and patches of fog that temporarily blind riders when a gazillion lumens bounce back into their bloodshot eyes and the ‘Swann 24Hour’ remains Australia’s toughest single test of stamina and endurance.

24 Hour Legends

Comparisons between riders of the twenties and thirties and today’s hot shots is totally ludicrous in an event where mechanical knowledge once outweighed the importance of riding skills, and sheer strength was more critical than athleticism. However what is obvious is that true legends dominated the results during their prime.

Charlie Moyle and his brother Jack were champion riders throughout the entire first decade of the 24 Hour. Totally proficient as outfit pilots or solo riders they accumulated 5 sidecar plus 3 solo victories. Both the Moyles owe much to Angus Leich who swung for Charlie in his 1926 victory and for Jack when he won seven years later. Between those occasions Angus enjoyed back-to-back solo victories making him arguably the most versatile competitor in the event’s history.

Harry Butler was already a veteran when he entered the inaugural trial in 1924 amassing 3 wins piloting an outfit before retiring after his 1939 solo victory. Harry’s reign also provided Les Fredericks with a taste of victory when he swung from Harry’s Harley in 1932. Les returned on a Triumph and savoured a hat-trick of wins immediately prior to the second world war and a further three wins when the 24 Hour was resumed in 1947. But his most outstanding feat was as the only survivor in the 1951 36 Hour Trial riding a Norton 500T solo – on which the rims had been relaced down to 18 inchers so his feat feet could touch the ground.

Ted Holyoak was another whose career spanned the war with 5 wins before hostilities (in one of which he was the only solo to finish) and bounced back with a final win in 1947. Ariel addict Ron Badger was another who may have enjoyed more success if not for the war. With a succession of 4 sidecar victories – each with a different swinger – Ron proved as competent in the bogs as he was on the bitumen. It was another Ron who managed a record of 4 straight victories with swinger ‘Milky’ Reed between 1948 and 1951, the last being the only outfit to finish the unique 825 mile, 36 Hour Trial. The records don’t list what marque Ron Ophel rode to achieve these victories but it’s a safe bet it wasn’t the BMW he rode on his later back-to-back wins in 1954/55.

Frank Gallery’s 4 wins were accrued at a time when the trial was still ‘cleanable’ and only a total of 6 minutes prevented the unlucky rider from making it six in a row from 1948 through 1954. Terry Holding was another who proved capable of winning on whatever was put under his bum, with solo victories in 1959/60 on a Honda followed by a Norton powered chair in ’61 and an Ariel chair in ’62.

There was nothing confusing about Peter Millsteed’s solo victory in 1963 – he was the only rider still mobile after 11 hours – but his subsequent wins over the following four years were ‘shared’ with Dennis Weichert (5 wins from ’62-’67) Lloyd Laing (’64, ’66 and ’67) and the eternal champion Jim Dowsett (’65, ’67 and ’70). Once the ‘uncleanable’ paddock sections were inserted Jim went on to a further 4 solo wins.

From that point on the record book became a lot clearer with (generally) only one solo winner and one outfit winner each year. So when Steve Jarvis took the hat-trick on his Honda in 1977/8/9 the results were clear cut. Steve was followed by Kevin Long with wins in ’85, ’86 and ’89, David Holt ’90, ’91 and ’92 and Andy Haydon ’94, ’98 and 2001.

Then along came young Shane Diener with a win in 1993, a hat-trick in ’95-’97 followed by five in a row between 2004 and 2008. It would be easy to say that Shane’s record will never be beaten (especially since he’s still competing) but that was said about Peter Millsteed and Jim Dowsett; and now the event is getting even more attention from interstate and offshore; for example Kiwi Chris Power ran third in 2009 second in 2009 and took a hat-trick over the past 3 years.