The Gregg Hansford versus Warren Willing battles define the ‘seventies period of Australian motorcycle racing. Yet despite prodigious skill, both left careers unfulfilled… for different reasons.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Rob Lewis, Michael Andrews, Warren Penney, Jim Scaysbrook

26-year-old Gregg Hansford was already a legend in Australia when he arrived at Brands Hatch for the F750 World Championship round in 1978. The four-times Australian Unlimited Champion had raced overseas semi-regularly since his international debut at Daytona in 1974, but the 1978 season was his first full foray into the big time.

Team Kawasaki Australia, basically consisting of Hansford as rider and Neville Doyle as manager and mechanic, had plenty on its plate for 1978. As well as contesting the 250 and 350 World Championship Grands Prix on the tandem twins, the team opted to fit in the Formula 750 races as well. Hansford’s KR750 triple was significantly down on power compared to the TZ750 Yamahas, but he made up the deficit with sheer ability. One week before Brands Hatch, Gregg had scored his first Grand Prix win – the Spanish 250cc at Jarama, in quite remarkable circumstances. The Spanish organisers had refused to give Hansford or another GP rookie, Kenny Roberts, a start because they were not on the official FIM grading list. After representations from both the Australian and American federations, the Spanish relented, but only the final day of qualifying remained. At the end of qualifying, Roberts topped the sheets by 0.1 seconds from Hansford! The Spanish organisers claimed they had never heard of Hansford, and perhaps communications were so primitive back then that news of Gregg’s sensational GP debut in Venezuela, one month earlier, had not filtered across the Atlantic. Nor the fact that of his 64 race starts in 1977, he had won 57. In South America, Gregg was not in the top 20 after lap one of the 350cc GP, yet four laps later he was leading, and had pulled an astonishing three-quarters of a lap gap when his KR350 spat out a gearbox oil seal just past half distance. A similar fate befell him while holding third in the 250cc GP.

Although Roberts was more than a little miffed by his treatment in Spain, Gregg didn’t appear unduly perturbed. He was probably thinking of his comfortable home back in Brisbane, swimming pool, girlfriend, nice car, that sort of thing. Home was never far from Gregg’s mind.

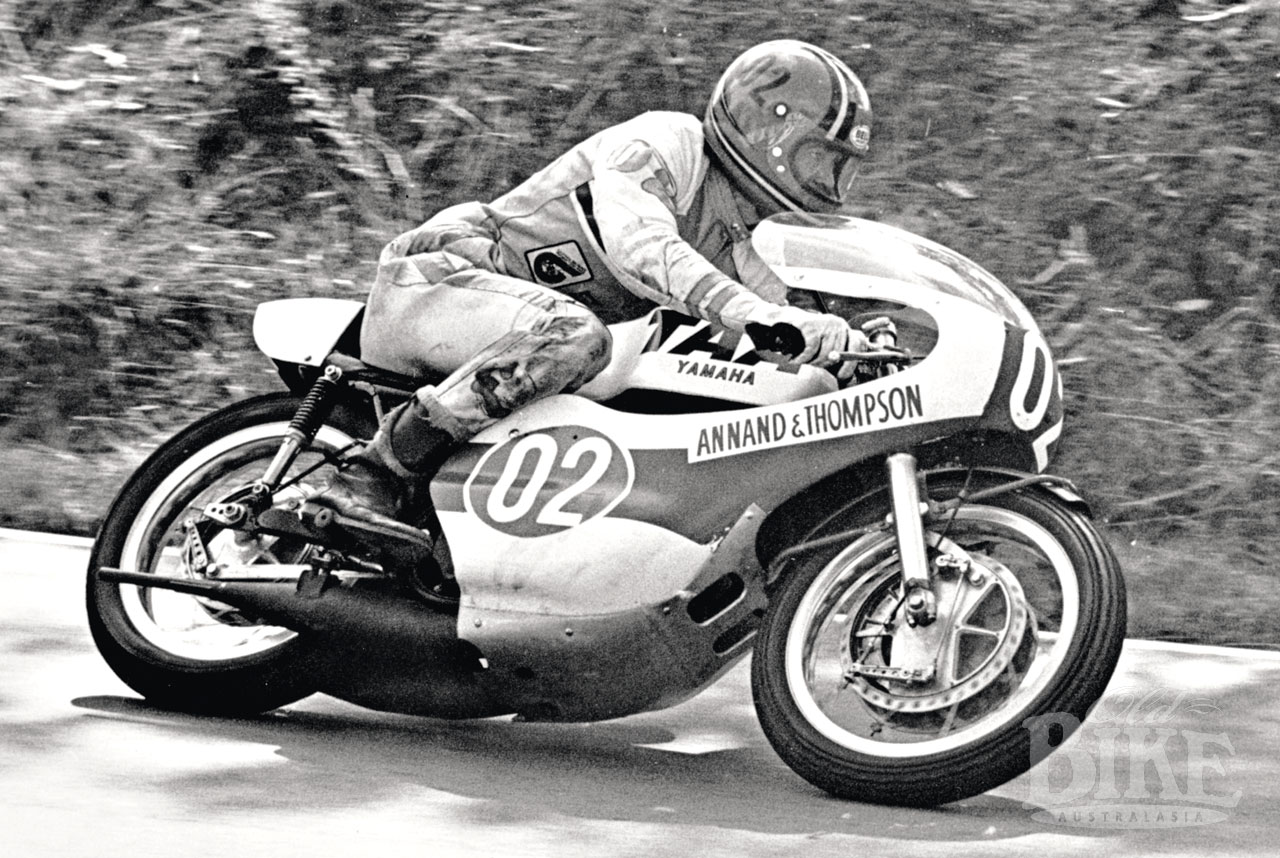

Gregg was born in Brisbane on April 8th, 1952, and discovered motorcycles at an early age, initially in dirt Short Circuit and scrambles. With help from John Taylor at Brisk Sales, he was given various Kawasakis to race, including an H1R 500 triple, on which he impressed sufficiently to be lured into the Yamaha fold on 250s and 350s provided by Annand and Thompson. For 1973, a new six-round format replaced the Australian TT as the official national title. Heading into the final round at Perth’s Wanneroo Park, Ron Toombs looked to have the 500 and Unlimited classes wrapped up, but fell in the 500 race, breaking his leg and handing the title to Hansford. With the Sydney veteran a non-starter in the Unlimited race, Gregg grabbed that one as well – a double champion at his first attempt.

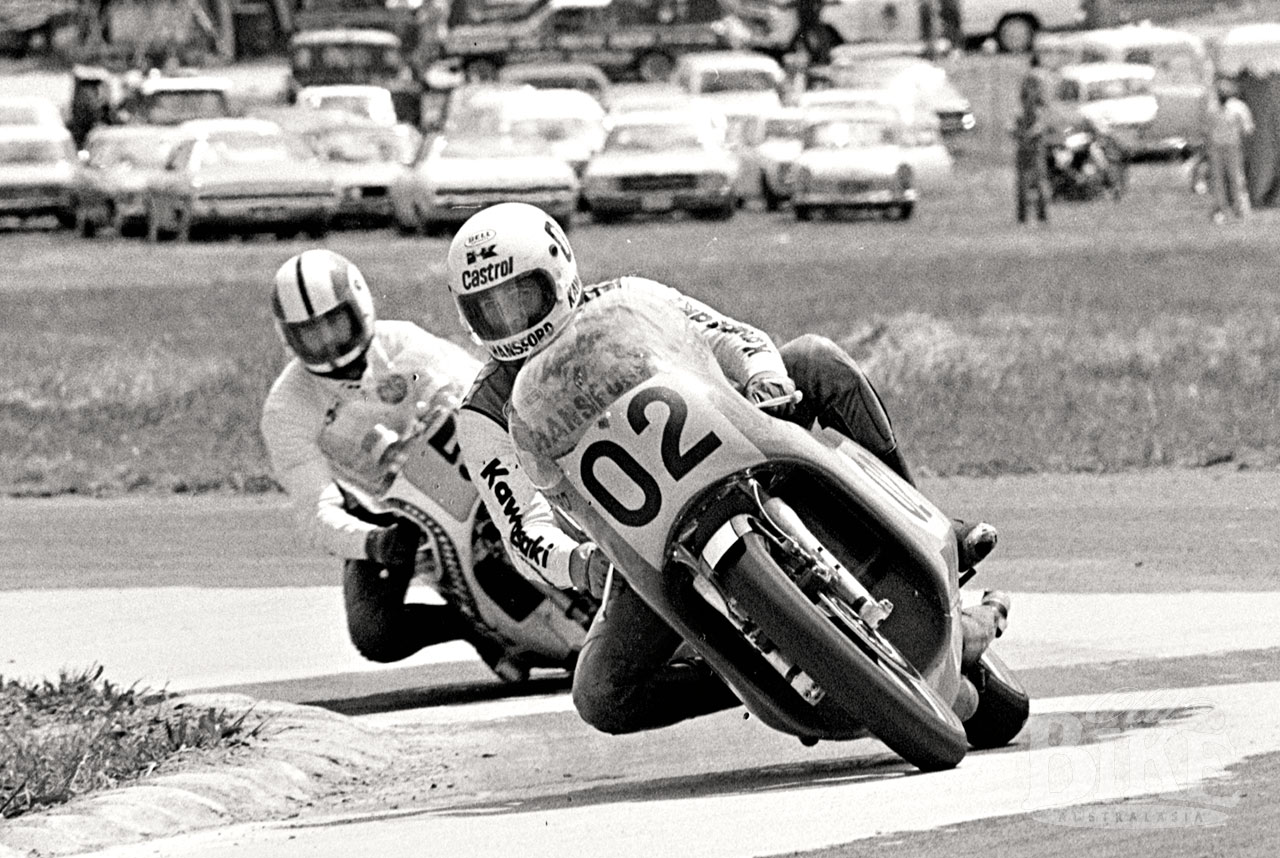

The TZ750 water-cooled four was Yamaha’s offering for the popular new Formula 750 class, and Hansford had one in time for the Daytona 200 in March 1974, where his great mate Warren Willing acted as his mechanic. By the time Bathurst rolled around in April, Willing had secured a TZ750 as well, and the pair staged one of the most memorable battles in the history of Mount Panorama. Willing won the main race in a blanket finish, and for the next two years the Willing and Hansford show captivated audiences across Australia. The rivalry intensified in 1975 when Gregg joined the emerging Team Kawasaki Australia, riding alongside Toombs on the air-cooled H2Rs, while Willing flew the opposition flag for the Toshiba-sponsored Yamaha Dealer Team.

Things began badly when Gregg hit a patch of oil in practice at Bathurst, breaking a wrist and a finger on the opposite hand, sustaining injuries to both wrists, but he was soon back into his stride to take out his third Australian Unlimited Championship on the trot. Under team manager Neville Doyle, TKA also ventured abroad in 1975, Gregg making his European debut at an F750 round in France, plus Daytona and Ontario in the US. Hansford and new TKA team member Murray Sayle delighted their employer by taking out the prestigious Castrol Six Hour Production Race at Amaroo Park on a Z1-B. In contrast, 1976 was unmemorable, but for the following season the team added the new tandem-twin KR250 to the stable, which now included the water-cooled KR750 which had been developed into a fast and reliable machine under Doyle’s guidance. Hansford took out both the Australian Championship classes with little trouble, while further forays into the European scene had Doyle thinking hard about an all-out effort for 1978.

With Kawasaki factory backing, the squad set off for Europe to contest both the 250cc and 350cc World Championships on the twins, plus the FIM Formula 750 title. It was a heavy workload, and as already detailed, fighting the bureaucracy was often as tough as the on-track battles. After the very public stoush with officialdom at the 1978 Spanish GP, Gregg let his ability do the talking. In the 250cc race at Jarama, Hansford admitted to following Roberts for a few laps in the race because he couldn’t remember where the circuit went, then pulled out and motored off to win by ten seconds from the Yamahas of Roberts and Franco Uncini.

The prospect of another Roberts/Hansford battle soon after at Brands Hatch, this time on 750s, sent the British press into near hysteria, but the punters weren’t overly interested in 750s and it was a sparse crowd that filed in for what turned out to be a cracker meeting. In the first leg, Steve Baker and Hansford were immediately disputing the lead, until Gregg dropped the model at Druid’s on the second lap and Roberts took over at the front. With no major damage to man or machine, Gregg was quickly on his feet and back into the fray, albeit in last place. In a dazzling display, Hansford ploughed back through the field to finish fourth, just behind Johnny Cecotto’s works Yamaha. For the second leg, Gregg was in a determined frame of mind, outbraking Roberts into Druid’s and steadily pulling away. The pair threaded their way through lapped traffic until they encountered Derek Chatterton, whose Yamaha had a sufficient speed advantage over the Kawasaki to re-pass on the run to Hawthorn’s. But Chatterton braked much earlier than Gregg and the Kawasaki ploughed into the rear of the Yamaha, sending the green machine spinning down the track for the second time that day. But Hansford had shown that no-one, Roberts included, could live with him under brakes.

That year Hansford won seven 250 and 350 GPs, but against his main rival Kork Ballington he had one major handicap – his physical size. Tall and broad shouldered, Gregg’s limbs stuck out in the breeze whereas Ballington’s compact frame fitted snugly inside the fairing. When top speed counted, it was no contest. In the 250 class, there was Roberts’ Carruthers-tuned Yamaha to contend with as well. A seizure in Belgium and a crash in the British 250 GP (which put him out of the 350 race as well) meant Gregg finished the season runner up in the 250 and third in the 350, despite taking a double victory at Yugoslavia’s final round. Gregg hankered for a 500, and there was one coming from Kawasaki, but when?

More of the same

1979 saw him saddle up once again on the KR250 and KR350, but on the smaller bike at least, it was a season to forget. The off-season had been spent in Australia, tyre-testing for Michelin, where Gregg had suffered two major crashes and started the GP season rather beaten-up. More falls followed in Europe and it was not until Imola, in May, that he scored a win, in the 350 GP. Mid-way through the season, Team Kawasaki Australia left Michelin for Dunlop, putting them, on tyres at least, on an equal footing with Ballington. Two more 350 wins followed, in Holland and in the archaic confines of Imatra, Finland. But the most dramatic weekend of all was spent in the motor home, not the saddle, when the works riders and some privateers walked out of the Belgian GP. The new, shorter 6.9 km circuit had come into being over a particularly harsh European winter, and diesel had been mixed with the bitumen in an effort to get it to cure in the bitterly cold conditions. In July’s heat, the surface proved virtually unrideable.

But the leftover from a dismal weekend was the formalisation of a threat by top riders to form a breakaway group to contest the ‘World Series’ in favour on the FIM World Championships, in 1980. Hansford was a staunch supporter of the plan, and stuck by his guns as the rival factions slugged it out. As history shows however, the World Series was doomed to be stillborn, and after rejecting an offer from Yamaha to contest the 500cc FIM Championship, Gregg but had no option but to remain with Kawasaki and wait until the KR500 materialised. There was little alternative but to return to the Australian scene for 1980, where Gregg took a 250/350 double at the Australian Grand Prix at Mount Panorama at Easter. He managed just one test session on the new 500, at Nurburgring, before the year was out, but it was enough to convince him and everyone else associated with the effort that the KR500 was seriously flawed in several areas.

When the bike reappeared for 1981, it had been completely redesigned. The international season began with the Imola 200 at Easter, and Gregg put the KR500 on pole. The race, however, was a disaster. Lapping a group of slower riders, Gregg hit a damp spot off-line and crashed heavily, breaking his tibia. He was sidelined for two months and missed the first seven Grands Prix. In the wet Dutch GP he struggled home fourteenth, complaining of severe handling problems, then the team headed for Spa. In intermittent rain, Gregg fought the recalcitrant KR500 until he could take no more, stopping at the pits and getting off the bike. For him, the race was over but the crew changed the front wheel and requested he use the remainder of the race as a much-needed test session. To change the wheel on the KR500, the disc calipers had to be removed and the pads pushed back, then the lever pumped several times to reset the pads. This was not done by Gregg nor by his pit crew, and he arrived at the new right hand diversion off the straight following Eau Rouge with a non-functioning front brake. The old unused part of the straight forms a run-off area and Gregg took to this, slowing the bike with the rear brake only, but a marshal had parked a car a short distance down the road. At about 70 km/h, Gregg hit the car, breaking the femur of the same leg that had been injured at Imola. More serious problems – blood clots in his thigh – quickly developed, and numerous operations over the next five years would be necessary to correct the damage. At just 29 years of age, Gregg’s motorcycle career was finished.

As early as 1977, he had dabbled in touring car racing, but by the mid-1980s and with his leg as good as it was ever going to be, he began to actively look for a drive in the booming Australian Touring Car racing scene. Former Canadian Allan Moffat, who became Ford’s top gun in the 1970s and 1980s, had long been a fan of Gregg’s and offered him occasional drives in endurance events in his own team cars. In 1988, the Moffat/Hansford pairing won the Sandown 500, the traditional lead-up race to the Bathurst 1000, in a Ford Sierra RS500. Teamed with ex-Formula One driver Larry Perkins, Gregg cracked the big one in 1993 when they drove a Holden Commodore to victory at in the Tooheys 1000 at Bathurst. Six months later he won again at Mount Panorama, this time with Neil Crompton in a Mazda RX7 in the 12-Hour race for Production Cars.

Despite these successes and his undeniable talent behind the wheel, Gregg simply could not land a regular seat in the V8-based Australian Touring Car Championship. In 1995, his luck appeared to have changed when he was offered a place in a new team owned by steel magnate Ross Palmer, driving a Ford Mondeo for the new Two Litre Championship series. But at Phillip Island’s opening round, he spun the car at Southern Loop and was rammed amidships, dying almost instantly. It remains a supreme irony that he lost his life in one of the safest forms of motorsport, after the majority of his career had been spent in the most dangerous. Gregg left behind his wife Julie and sons Ryan and Rhys, and new partner Carolyn and baby son Harrison. Both Ryan and Rhys have followed their father onto the track, racing in the V8 Ute series.

A lasting tribute

At the National Motor Racing Museum at Bathurst, a section of the vehicle display is devoted to some of the bikes on which Gregg made his name. The machine on which he made his international debut at Daytona in 1974 – the Yamaha TZ750A – is now owned by fellow Queenslander Graham Lampard. The bike has been restored to its exact Daytona specification, complete with the number 61 in place of Gregg’s famous 02. Various problems beset that effort, particularly handling worries on the notorious Daytona bankings. Kel Carruthers provided a set of Koni rear shocks which went part of the way to solving the handling dramas, but ignition gremlins eventually put paid to any result. The Yamaha, which had been purchased by Queensland distributors Annand & Thompson, was flown back to Australia in time for the big Easter Bathurst meeting. Gregg rode the Yamaha for the rest of 1974, taking the second of his four Australian Unlimited Championship titles with it. He also raced the Yamaha in the season-closing Pan Pacific International Series.

When Gregg jumped camps to Kawasaki for 1975, his TZ750A was sold to Gold Coast property developer David Hinks, who sponsored Rob Moorehouse on it for the next few seasons. Hinks purchased a new TZ750D for Moorehouse in 1978 and the A model was partly dismantled and the engine removed to be used as a spare if needed. Tragically, Moorehouse lost his life at Bathurst in 1980 and the ex-Hansford Yamaha lay dismantled and neglected until it was purchased by Graham Lampard in 1996. Fortunately, the rolling chassis was largely intact, even down to the Koni shock absorbers, but it still took several years until the old warrior was back together again. The restoration to Daytona ’74 specification is meticulous, right down to the recreation of the original stickers.

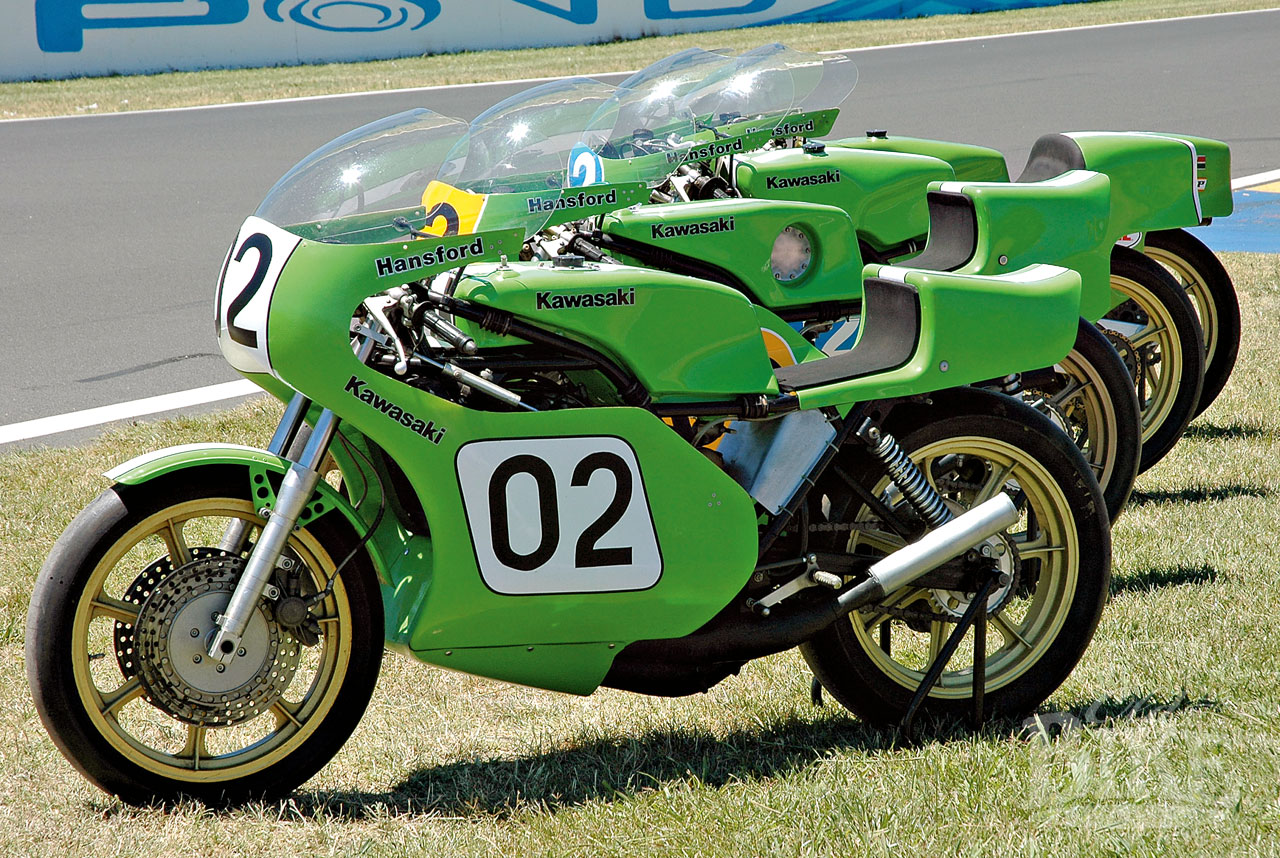

Gary Middleton and Gregg Hansford go back a long way – as school chums in Brisbane. Later in life, Gary built Gregg’s house in the suburb of Bardon. When the opportunity arose to purchase some of the ex-Hansford Kawasakis from Neville Doyle’s stable, Gary jumped at it. The most venerable of the four bikes Gary now owns is the H2R which served as Gregg’s introductory mount in Team Kawasaki Australia in 1975.

The H2R was retained for 1976 while the team waited for the new KR750, but even when the water-cooled machine arrived, it proved slower than the locally developed earlier model. At Bathurst in 1976, Hansford rode both the KR750 (which broke a gear lever in its first race) and the H2R, which proved to be no match for either Ikijro Takai’s works Yamaha or Warren Willing’s privately-fettled example. Throughout the rest of the year, Doyle worked his wonders on the KR750, considerably reducing the standard weight of 144 kg, but it was too late to retain his national title, which went to Willing. TKA took the KR750 to the Daytona 200 in 1977, and Gregg finished fourth in the first 100-mile leg. The second was cancelled due to rain. When Gregg and Neville Doyle departed for Europe in 1978 they took four bikes; two 250s, a 350 and a lightweight version of the KR750. The KR250 in the Middleton collection was delivered to the team late in the season, and Gregg rode it to victory at the Swedish and Yugoslavian GPs. Gary’s KR350 was the first of two Junior models used in the 1978 season, winning the French GP at Nogaro. At the conclusion of the 1979 season, all the bikes – three 250s and two 350s, were shipped back to Australia, and were still sitting in crates when Middleton began work on Hansford’s new home. With all the uncertainty about the ill-fated World Series for 1979, the machines lay untouched for several months, until it became clear that there was nothing for Gregg in Europe. The Middleton quartet is a reminder of the days when Hansford and Neville Doyle mixed it with, and frequently beat, the world’s best, and for Gary, a lasting tribute to his great friend.